A Different Kind of Play

There I was. I loved to play. I wanted to figure out how things worked. My dad would bring home old electronics from his work and we'd take them apart together.

In middle school I started a chemistry lab in the guest bedroom. It wasn't much, just a box that became a fume hood and some supplies from United Nuclear. Many notable incidents happend in that room, including a metal fire and an uncontrolled release of a corrosive gas.

One year, I decided to enter the local science fair with one of my lab projects: setting things on fire with chemicals. I never thought I'd win anything, but I got highest honors. It made me realize that people could appreciate the things I was doing.

My second project was about extracting caffeine from drinks using a distillation setup in my bathroom. To be honest, I was in seventh grade and the cheap distillation equipment I'd bought from the internet was just cool to play with. But somehow I watched as my project went further and further along in the Broadcom MASTERS competition until I was named a finalist. Broadcom MASTERS is a national science competition that picks 30 young scientists to present their work and compete as teams. That week I met people who played just like I did. We went on research boats and played truth or dare in our coach bus. From the other finalists, I learned about robot arms and bee farms and microwave ovens.

Taking Myself Seriously

When I got to high school, I started to realize that it wasn't normal for people to leave that small town where I grew up. As I went through my classes, the week with the Broadcom MASTERS people stuck with me. I wanted to be with people like that. I stayed up late nights and took too many AP classes. I made another workbench for electronics, where I tinkered with any broken electronic device that I could find. I also created a safety stove that turned off when a pot boiled dry.

I took these projects to the international science fair twice. Although I might have been someone notable at the local science fair, the sheer scale and accomplishments of some of these international science fair projects caught me by surprise. Seeing what everyone else was doing, I thought I had to work much harder and craft bigger projects that would actually change the world. I was a high schooler. I wasn't going to change the world, or any slice of it. But I still believed in it.

This new thing called "Artificial Intelligence" was beoming more accessible to someone in high school. I started training models on my home desktop computer. When senior year hit, I'd learned a bit about AI, but I'd forgotten what it was like to be in seventh grade and crouching over a bubbling distillation setup. Back then, I wasn't looking to do better, be better; I was just looking for crystals of caffeine.

I applied to Stanford just like all my other friends at school, because it was funny and tickled our what-ifs. On an early evening in March, as the pandemic spread throughout my state, I opened my admissions letter. My dad was cooking dinner and my mom was cleaning. I saw the streamers appear on my letter. I graduated in mid-July by walking around the track. COVID was a lonely time.

Learning to Play Again

The momentum of high school science fairs took me directly into college wanting to start work in a research lab immediately. I emailed all the AI professors and heard back from only one. I joined Chelsea Finn's lab in the winter of my freshman year, where I worked on making robots listen to sounds. Even though I knew some AI, the challenges of robot learning was entirely foreign. I stayed up late, watching lectures on probability and reinforcement learning. I dove into giant codebases with the help of an amazing mentor, Suraj. In the darkness of the pandemic, sitting at home, this research made me feel less lonely.

We submitted that project in my sophomore year and we worked so hard to get it accepted into a top robotics conference. My collaborator Olivia and I presented this work in the summer of 2022 at Robotics: Science and Systems. Sitting through the other presentations, I couldn't understand very much. But unlike the international science fairs in high school that scared me into doing larger and larger projects, this conference showed me what was possible. As I sat with all the people in this field, their research questions made me excited. This idea of training robots like humans and animals hit an emotional chord beyond the technical.

I started my second project after that conference and it lasted until winter break. We were shooting for a deadline in January and I needed many more robot experiments. When campus closed down for winter and I flew home, I carried a little robot in my luggage. Sitting at my childhood computer desk, I spent evenings collecting data and evaluating the robot. I made a toy setup and then tried to show how resilient my robot was. In those hours, the robot felt somehow alive. It was my own.

As I became more familiar with the robot field, I started teaching robotics to high school students through the Stanford Splash program. It was hard to learn how to teach. I had to wind back the clock and imagine what I wouldn't have known. I let the kids train me with a clicker to show core learning concepts.

They'd come up to me after the class and ask me about college. In their eyes I saw admiration but also the same desperation that felt so recognizable. I told them what they wanted to know, but I hurt for them, as I hurt for who I was in high school.

No Longer an Accident

By my senior year, I'd started working on a third research project. The prospect of a PhD felt much more real and much more desirable. I applied in late fall from a small shared dorm room because Stanford had messed up my housing assignment. A few months and many interviews later, I got a call that I dismissed as junk. Then I got a Slack message from a professor asking me to pick up my phone. There, in the robot lab, I learned that I'd been admitted to Stanford as a PhD student. I was admitted to other places too, but I ultimately decided to stay. At Stanford, I was awarded the Knight-Hennessy fellowship for my work in writing and research.

Throughout my whole journey growing up, I let things happen to me. They felt like a series of fortunate accidents, which often made me feel like I wasn't supposed to belong. But as I made my way through interviews and school visits, these feelings started to fade. When I opened up my admissions for the fellowship and months later walked into my PhD orientation, I was telling myself that I was in the right place.

Here I am now. I work in a robot lab trying to make robots better for adaptation. As of summer 2025, I've submitted my first PhD project to a conference and I'm doing the work I've always wanted to do. In the light of morning sometimes I think that I'm not doing enough. Sometimes I see what my college friends are doing and wonder about other paths I could have taken. Sometimes I see people getting married and wonder if this program is keeping me too young, shielding me from adult life. But I catch a feeling, that feeling of standing over a bubbling condenser and smelling the organic solvents in my childhood bathroom. I'm standing over my robot dog, wondering if it will follow my instructions. I show people the robot dance. Here you are, I say to myself. And there you'll be.

One drop of water.

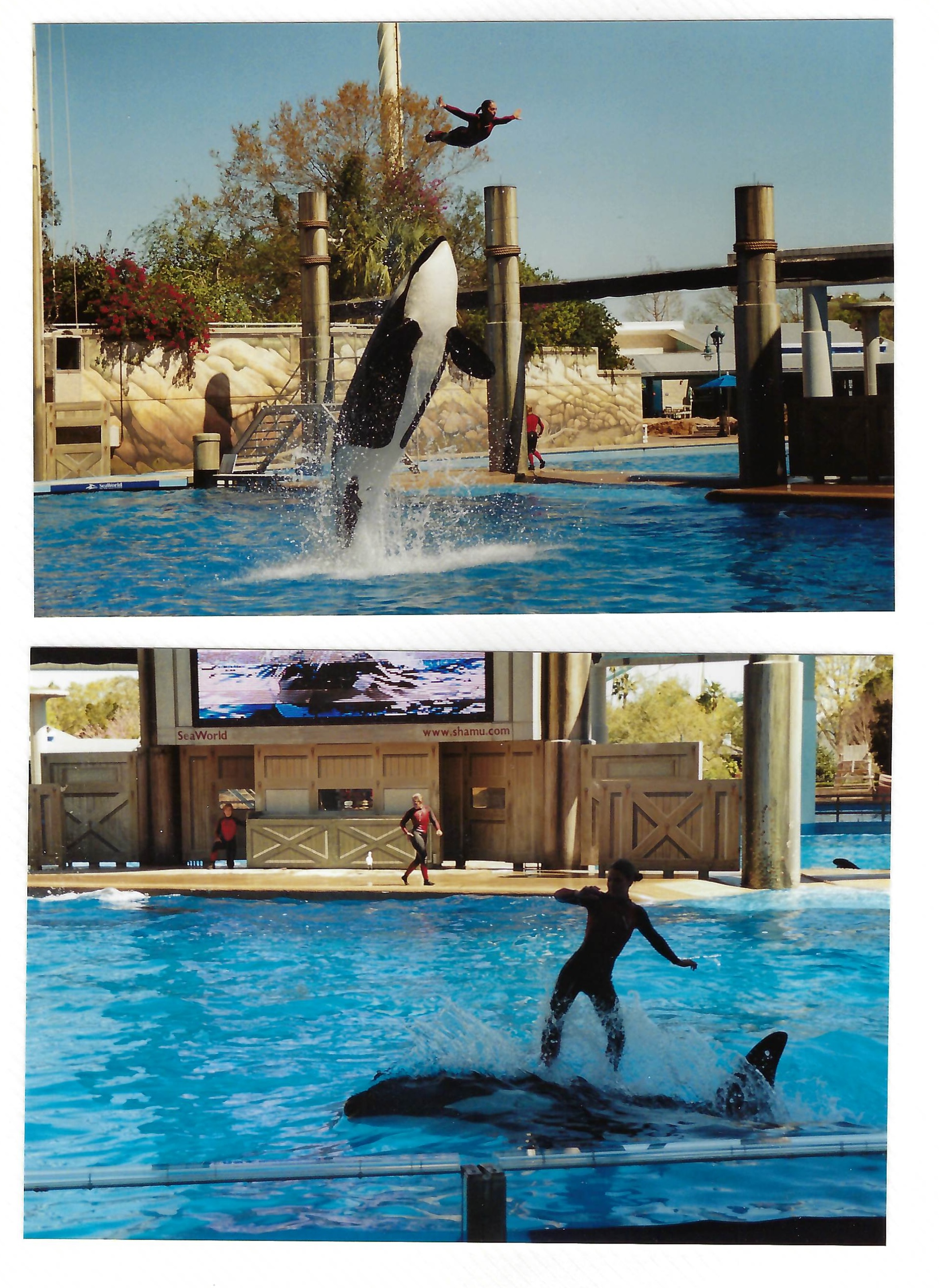

It was our first family trip to SeaWorld. I don't remember any details, but I remember the feeling of watching the trainers ride the whales like surfboards. It felt so impossible and beautiful.

We made more family trips to Florida and California whenever my dad traveled for research conferences. I watched the iconic "Believe" whale show at SeaWorld many, many times. It was about a boy who fell in love with whales, and I felt seen. I dressed as a killer whale for halloween one year. I told everyone whale facts. Everyone wanted to hug me.

The interrupted dream

Maybe it was because of a tragic 2010 incident where a trainer lost her life, maybe because SeaWorld had become controversial, or maybe because I was a chaotic little kid with many issues of his own. I hugged a plush whale to sleep every night. I listened to whale show songs on loop. I dreamed of becoming a killer whale trainer. Whatever it was, my interest in whales transformed into an obsession. My friends called me Orca Boy.

For a brief few months in middle school, I joined an online whale fandom. We made video edits of whales set to music. That same summer, my friends at a summer science camp made fun of my whale obsession, telling me that I should go marry a whale. That's just teenage boys being boys, but after that incident, I started feeling a deep shame for all this whale stuff.

You might be able to imagine how an online animal fandom might get a bit weird. As I grew older and saw how different this obsession was to the outside world, I started taking down my whale posters and removing my whale videos from YouTube. Discarded, but not forgotten.

There you are, Peter

Over the summer of my senior year, I embarked on a writing project (see other tab) and my research led me to a killer whale trainer who had gone to my same high school. Our dads were colleagues at Syracuse University, and we both loved the village ice cream shack, Sno Top. Lyndsey and I became quick friends, not just because of our shared roots but because we were both repairing our relationships with ourselves. I was recovering from various events in my childhood (see other tab), and Lyndsey's best friend had been killed by a whale. I had the privilege of hearing her work through her past, both beautiful and tragic. We talked for hours.

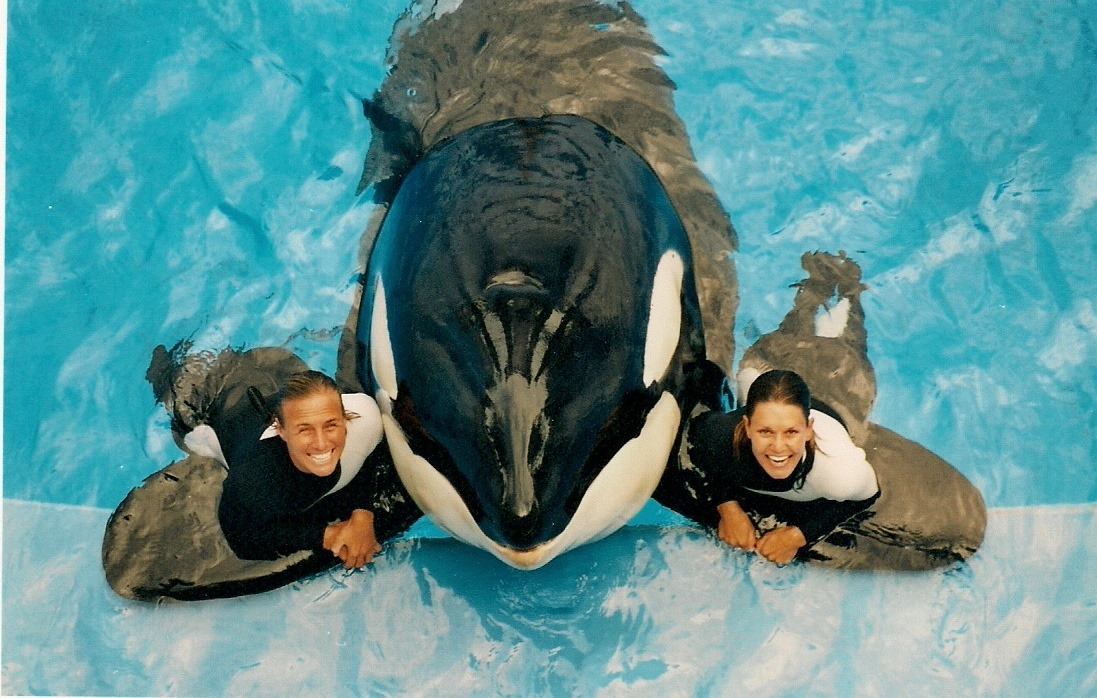

My friendship with Lyndsey gave a place for our love for whales to grow. I visited SeaWorld San Diego for the first time in nearly a decade, where I snapped a selfie with a whale trainer named Elizabeth. We talked about training robots and training animals. Many things had changed since the whale shows of my childhood. I felt like many of the feelings were tied not to a place but a time, and that time had long passed. But it still lived on in a different way. I felt that as I walked out of SeaWorld that late November night.

During spring break of my college sophomore year, I flew to Florida and stayed with Lyndsey for a whole week. She took me backstage where we almost got in trouble because someone saw my name. As you will see in another tab, my writing project was about marine parks and animal trainers. Because of past media coverage, people feared the worst. Working through this craziness strengthened our friendship. It also showed me the darker sides of the marine mammal industry, a side fueled by fear and disposable employees.

On a whim, I decided to fly down to San Diego in the week before my college junior year and join a workshop on animal training. I thought I was going to take notes, watch presentations, and leave. Instead, on the first morning, I was approached by a guy called Eric and a group of other people. They asked if I wanted to go for coffee. They were Navy dolphin interns, and during that whole workshop they adopted me and treated me like one of their own. It was the most included I'd ever felt in my whole life.

Something Far Greater; Something Far More

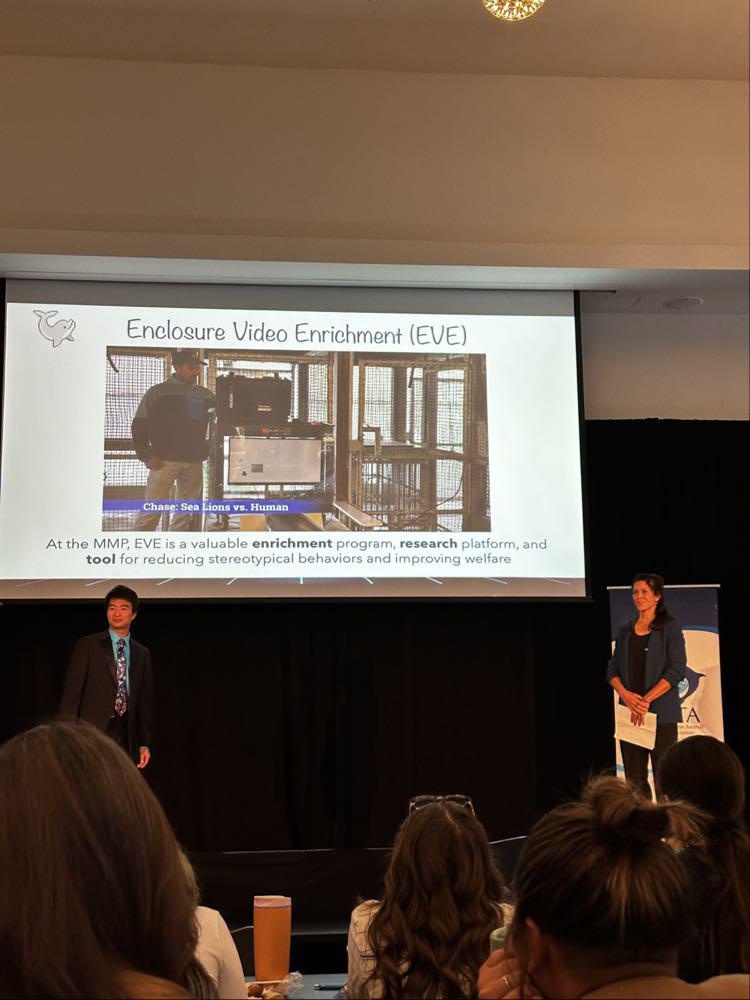

I did get more of what I felt I needed. Between my undergrad and Ph.D., I spent my summer interning for the Navy Marine Mammal Program (MMP), where I worked hands-on with dolphins and sea lions. I watched as dolphins played video games. I designed a computer vision-based game controller for a special dolphin who goes by the callsign CHE. The MMP showed me what a really well run facility looked like, filled with so many animals and an abundance of resources. This experience firmly convinced me that marine mammal facilities need to continue existing for all of prosperity.

That summer, I learned that SeaWorld was trying to get their whales to play video games to improve their welfare but they were struggling to design a good game controller. I happened to know how to track things using depth estimation. Using a camera I borrowed from my lab, we were able to show good enough results to convince corporate that the video games were feasible.

This experience reminded me of the glorious accidents that had been a part of my whale journey. If Lyndsey hadn't come into my life, I would've kept whales in the rearview mirror. If Eric hadn't invited me to coffee, I probably would never have been a Navy dolphin intern. If I weren't an intern, I would have never known about the whale video games.

My supervisors at the Navy let me be a part of their research presentation at a large conference for marine animal trainers. At that conference, Nicole (pictured) and I discovered that we'd been sitting so close together during that animal training workshop. We were ships in the night until the time became right. We got second place in the research presentation category. We also won honorable mention for audience choice. We danced to APT. and the open bars made everything beautiful again.

This is me now. Here's Hannah and Hunter and a big dog named Shouka after she'd been playing our video games. If you've been following the things going on in the marine mammal industry you'll know that it's very messy. I see that and understand that. But the good people of this industry made me who I am today. They made me into someone who I'm proud to be.

My Alt Ego

I work my day job as a researcher and my side hustles with the dolphins. But early in the morning, I'm a writer. I studied creative writing (minor) in undergrad, and I worked as a Senior Producer for the Stanford Storytelling Project.

During the pandemic, I did a ton of research on the history of captive whales & dolphins. It wasn't for any assignment. I just liked whales (see other tab) and was curious about their interactions in the human world. I worked on it for hours every night. By the end of the summer, I'd written 250 pages.

With help from the Stanford Storytelling Project, I turned this initial research into a book idea, focusing on the oral history of animal trainers. Oral history is the telling of personal stories through extensive interviews of subjects. They are the opposite of extractive journalism.

On this journey, I went all over the place. I looked at the philosophy of human-animal interactions, the literature, and the science. I took a class that felt more like a bible study except we were reading Moby Dick.

Using my oral history work, I was able to obtain an academic grant to travel and interview people that represented the counternarrative: the stories of people who supported responsible zoological institutions in the face of animal activism and public outcry.

Having engaged with many different ideas about animal captivity, my academic and personal journey led me to support institutions with animals in human care, including marine mammals like whales and dolphins.

My academic grant also supported a trip to the largest gathering of anti-captivity activists, held in Friday Harbor, WA. Although I held extremely different views from these people, they treated me very well and I even got lunch with some big-name activists. The trick is, don't trick people. Tell them what you believe and show that you're willing to listen.

Being a "Normal" Writer

My main writing project is very full of whales and dolphins, but the oral history I do is universal. I helped workshop many other narrative stories produced by the Stanford Storytelling Project. I even went on live radio to promote the art of oral history.

Writing is an evil thing. It has a shallow learning curve at first that makes you feel like writing is easy. Then the curve shoots upwards and leaves you thinking that you'll never be able to write as good as a published author. I'm very grateful that a collection of great writing mentors were there when I reached that sharp curve. Some of them pushed me up. Others helped me see the ground below. All of them honed my writing craft. Adam Johnson was my most influential mentor, and he continues to help me build my writing chops. Oh, and he's a Pulitzer prize winner.

When I write, I write because it heals me. But once it's out, I'm happy to share it with the world. I've been very honored to receive two Stanford undergraduate writing prizes, including third place in non-fiction and second place in fiction.

What am I working on now?

For a brief time, I worked with someone on a series of op-eds about animal welfare and corporate responsibility. I enjoyed the process, although I've realized that I'm not interested in investigative writing. I don't do FoIAs; I ask people about their lives. Unfortunately, this former collaborator no longer shares the same views as me. Our personal journeys are different, and I maintain my support for responsible zoos, aquariums, and marine parks. I wish her the best and look upon this time fondly.

I'm still interested in writing op-eds about things from my research (robots and whales) that I want people to know. I'm also looking to publish longer form non-fiction about these fields, especially about animal and robot intelligence.

Of course, I'm still working on the animal trainer book, although I'm not trying to push on it as quickly as I once did. There are many reasons. The biggest one is maturity in the subject. The more nuance I gain from these stories, the slower I go. My literature review now spans close to ten thousand articles. But another big reason is that I can no longer claim to be a neutral oral historian who observes a population of people. I have been part of this population. I've worked with dolphins and I'm continuing to be a part of the marine mammal industry. It's impossible to be unbiased now, but perhaps that's the uniqueness of my story.

Since the start of my Ph.D., I've been setting time aside every morning to work on fiction writing. Because I like painful, hard things, I've been working on short stories. Working on brief character encounters brings me a lot of joy. When I finish my writing session, I'm still thinking and feeling like these people. I hope that I'll be able to showcase a finished story soon.

The Shell

I'm from a small town of around four thousand people. I grew up on back roads, starry nights, and country music.

My parents immigrated to the US for a better education. Here they were, back in Pittsburgh. My dad would become a professor at Syracuse University, and my mom would raise me in a two-story house behind the high school.

I was an only child. I sometimes played with the neighborhood kids or the friends from school. But for the most part, I liked to be alone. I liked to play with my own toys.

The Cave

My parents tried very hard to raise me in a world that was always foreign to them. But they were also fighting their own challenges. Because of this situation, I had to be hypervigiliant towards a certain person's demeanor, temper, and desires. An emotional shield was easier to live behind.

My parents tried very hard and in many ways they were great parents. But they also left me with many things that I've been working through for much of my adult life.

When I first left for college, I discovered that I felt things very deeply, especially darkness. It all came at once and I felt like I was drowning.

Sometimes I felt extreme loneliness. I felt it when I was with other people. I felt like I could never be fully understood.

Other times I felt nothing at all.

Growing up, I knew how our house glowed at night. You should have seen what we did during the holidays. The lights were everywhere.

More things ended up happening with my family since I left for college. I watched as someone descended into a world of fantasy, believing that the house was filled with surveillance devices. I watched someone leave the American dream behind.

In the few times that I've returned home on holidays, I saw the same lights, but I also saw the new security cameras and one-way security film and tinfoil taped to the walls.

I felt like the lights didn't shine for me anymore.

The Blossom

It took many years to understand my depression and what it meant to love myself again.

The darkness is an animal. It has no language, just a whole past life and all the feelings in the world. It was my dog, emaciated and fearful. I had to teach it to want. I had to bring back the shine in its eyes.

The best lessons came from unusual places. Jimmy Buffett's music, for example. Not the beachy fun stuff but the darker songs like One Particular Harbor, or He Went to Paris.

I saw myself mirrored in people like Lyndsey (see other tab) and other friends, especially friends who were much older. When a group of strangers adopted me at an animal training workshop, I didn't push back. For the first time, I didn't feel like disappearing into a crowd.

I spent long hours walking through sadness, looking at night skys and deep ravines. I didn't know when and where I'd feel deeply, but I learned to welcome it when it came. I carried a voice recorder in my backpack.

To be brutally honest, I still never found a place in my friend groups during Stanford undergrad. And it's definitely my fault; it was just so hard to let people in.

In the summer before my Ph.D., I did an internship with the Navy dolphin program. I found that the outside world was so different than the university bubble that I'd come from.

It's rough and tumble, full of heartbreak and messiness, but so real. Me and the other interns went out every Thursday to a wine place downtown. We got really drunk and we talked like nobody else cared who we were. We got gelato. We crashed at people's places when we were too drunk to go home.

These are still the closest friends that I have. They're my ride-or-die, full stop.

I wish that taming my dog was as easy as finding the right people. It isn't, but these people from the Navy dolphin program were an irreplacable part of my journey.

Healing my inner dog meant discovering new things about who I am. For example, that I'm actually a little crazy. I should've known from my love for fire and explosions as a kid. I want to take up space, command attention at times.

The Seed

I discovered that healing this dog was never a one way path. There are steps forward and great backward tumbles.

Many times the darkness comes back to me. It's always there.

But I remember the people I've met.

Sometimes the dog whimpers.

Sometimes the dog hides.

Sometimes the dog has slobber on its mouth and a tail wagging so hard it whistles in the air.

I tell my dog, I love you. I love you however you are. I love you because you're here.

And I'm starting to believe that the light still shines for me.